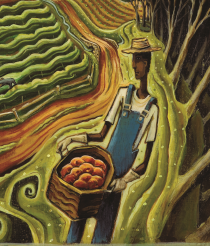

As the sun rises over Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., a flatbed pickup drives slowly between rows of peach trees. As it passes, Jamaican farm workers hand up baskets filled with firm, rose-tinged fruit. Most of these men arrived in April to start the growing season and will return to Jamaica in December when their visas expire.

In a nearby greenhouse, a short woman wearing a faded red baseball cap wades between two waist-high flooder tables. Her hands move quickly from one potted Poinsettia to another while nimble fingers pluck all but the most prominent stems. Everyone calls her Leti and she has been making the annual trip from Mexico to Canada for 20 years.

Meyers Farms employs more than 80 foreign nationals at any one time. They come from Jamaica, Mexico and Guatemala on temporary visas provided through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP). Many return year after year, spending no more than four months in their home countries.

“We Canadians who are not involved in the food production process have no idea how much work goes into the operations on a farm,” says Katharine Masterton, program coordinator with the national church’s Justice Ministries department. Last June, Masterton organized a three-day trip to Niagara-on-the-Lake for Presbyterians who were interested in the complicated issue of foreign workers in Canada.

“I’d read statistical stuff on temporary foreign workers, but I had never been on a large-scale commercial farm and I had never met anyone who was involved in the labour process,” Masterton says. For her, it was necessary to put names and faces to what can otherwise be just another Canadian issue.

“It’s so easy to be black and white about it and to not see that it’s one big complicated story. There are names and faces behind it all.”

Farmers across the country face a domestic labour shortage as the need for labour rises while the number of Canadians willing to do the job continues to fall. Programs that bring foreigners to Canada aim to fill the gap.

SAWP is one of four programs run by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC). Together the federal ministries also run the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, the Live-in Caregiver Program and the Project for Occupations Requiring Lower Levels of Formal Training. Each program involves a different industry, but all bring in foreign workers on temporary work permits.

Although temporary workers accounted for less than one per cent of all full-time workers surveyed in the 2006 census, there are about 400,000 temporary foreign workers in Canada each year. That’s a striking number considering about 250,000 new immigrants are admitted yearly. According to the CIC, the Temporary Foreign Worker Program is the fastest growing reason for temporary workers to be admitted into the country.

Compensation for foreign workers is complicated. While stipulations vary by province, employers normally cover the initial costs of travel and housing, but a portion of those costs (along with other things such as meals, insurance premiums, and work visa fees) may come off the worker’s pay cheque.

Alfredo Barahona is a migrant rights program coordinator with Kairos Canada, an ecumenical social justice group supported by the Presbyterian Church. He says it is difficult to evaluate the wage of a foreign worker because there is no Canadian equivalent to compare it with.

Alfredo Barahona is a migrant rights program coordinator with Kairos Canada, an ecumenical social justice group supported by the Presbyterian Church. He says it is difficult to evaluate the wage of a foreign worker because there is no Canadian equivalent to compare it with.

“One of the reasons why workers are brought into any field is because employers are saying that they cannot find a Canadian who will take the job. You are not likely to find any Canadians in the field, so it is hard to compare wages.”

According to the HRSDC’s website, the employer must pay seasonal foreign workers one of three rates of pay, whichever one is highest:

the provincial minimum wage;

the prevailing wage identified by the Government of Canada; or

the same rate the employer pays Canadians for doing the same type of work.

And the employer must make additional payments for overtime.

However, according to Stan Raper, national coordinator for the United Food and Commercial Workers’ Union, the government’s statement is deceiving. “Labour laws fall under provincial jurisdiction and agriculture workers in Ontario are excluded from specific provisions of the Employment Standards Act. The hours of work provision and vacation with pay are all sections of the provincial Employment Standards Act, which, for farm workers, are out of reach.

“Until the federal government implements national standards for agriculture workers or puts their protection under specific federal regulation they are all talk with no ability to act.”

In November 2010, the UN International Labour Organization criticised Ontario for violating the human rights of its foreign and domestic agricultural workers. The organization found fault with Ontario’s Agricultural Employees Protection Act, which allows workers to organize but prevents them from collective action or bargaining.

Without an effective union, Ontario agricultural workers cannot challenge executive decisions, working conditions or their role in a business unless they do so as an individual. That’s risky for foreign workers, Barahona says. They not only risk losing their jobs, they also risk being sent home.

“If there is a disagreement and the worker complains, the employer may decide that he will be sent back. That happens a lot. Workers are just shipped back, end of story,” Barahona says. “If your employer labels you a troublemaker, that’s going to raise flags for others and you may not be able to come back.

“Workers are tied to a particular employer,” Barahona adds. “If, for whatever reason, your employer doesn’t want you there, you cannot simply go to another employer. You have to apply for another permit and you don’t know how long that is going to take.”

“Signing a contract is signing away your rights,” says Troy Ebanks, a young electrical engineer and proud Jamaican. “But no contract is just as bad. There’s no security.”

Working in Canada is a tradition in the Ebanks family. Troy’s father was a seasonal agricultural worker for 27 years and his brother works on a farm in Niagara. After finishing his studies in Jamaica, Ebanks applied to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

Working in Canada is a tradition in the Ebanks family. Troy’s father was a seasonal agricultural worker for 27 years and his brother works on a farm in Niagara. After finishing his studies in Jamaica, Ebanks applied to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

“They wouldn’t take me at first,” Ebanks says. “They said I wouldn’t go back to Jamaica when my visa expired.” However, with some perseverance, he received a two-year permit with a cucumber grower in Leamington, Ont.

Ebanks recalls the close calls that marked his first few weeks on the job. A co-worker’s foot was crushed under a piece of heavy farm equipment. Another worker nearly lost an eye. After the first accident, Ebanks and his co-workers received steel-toed boots. After the second, everyone was given safety goggles.

“I asked my supervisor what the boss was doing to prevent injuries, but he wouldn’t give me a clear answer,” Ebanks says. “He said the conditions were good.”

Ebanks also asked why chemicals were sprayed while the workers were in the greenhouse and why the heat was off when the workers arrived on cold winter mornings.

Less than two months after speaking with his supervisor, Ebanks lost his job.

With more than a year left on his visa, Ebanks decided to stay in Canada. He moved to Niagara and found work in a vineyard. However, because his permit is tied to the company in Leamington, Ebanks works without the benefit of a contract.

Even with a permit, foreign workers don’t always enjoy the rights that are available to other Canadian residents. For example, workers are entitled to health care and workers’ compensation, but many illnesses and injuries go unreported.

Michael Coley has been coming to Canada since 1999. In early August, he experienced severe chest and arm pain. Rather than talk to his supervisor, Coley kept his worries to himself.

On Aug. 18, Coley had a minor heart attack. After removing a blood clot, his doctor advised four days of rest and no less than six weeks of light work. Since there is no light work on a farm, Coley’s employer planned to send the ailing worker home. However, Coley refused, arguing that he was not fit to fly back to Jamaica.

Sitting on the front stoop of the house he shares with his co-workers, Coley struggles to tell a story that has left him feeling bitter. “After all I went through, they were sending me on my way home to die. That tells me they simply don’t care. As long as workers are doing their job, they are fine. When you are sick, you are of no more use to them.”

“Workers fear being deported if there are any imperfections or dissatisfaction in their capacity to work,” says Janette McIntosh, Vancouver’s Kairos contact, and member at West Point Grey, Vancouver. “With that fear looming there are some hidden tragedies.”

Every province has standards of employment that are meant to prevent such tragedies, McIntosh adds. The problem is, there is currently no way to ensure standards are being met.

Barahona agrees. “There are good employers and there are workers who have a good relationship with their employer. Unfortunately, this is left to the individual employer because the mechanisms that would ensure fair treatment are not there.

“There should be a government employee who investigates each worksite and there should be non-government advocates to verify that the work is being done. … Mechanisms will ensure that workers receive the support they need without fear of being laid off or sent home.”

“The reality is that the workers want to come,” Barahona continues. “They need to come and we need them to come. So, if we need the workers and they are making a contribution to our economy and society, why do we have to keep them as disposable commodities? These are men and women like you, like me. They are God’s creation and are entitled to everything that we enjoy here in this country. Everything you want for yourself, wouldn’t you want that for someone else?”

In the fading light of Friday evening, the Meyers Farms staff gather for cold drinks, a few laughs, and a chance to celebrate the end of another workweek. It’s a tradition that extends back to when farm founder Jim Meyers hired his first migrant workers.

“He was the heart of this place,” says Arnie Vlaar, who manages greenhouse production. Jim Meyers died last summer and Vlaar says the farm is going through an emotional transition. “Even now we are discovering little things he would do … He was always out working the fields with his hired hands.

“He was very proud of his Mexican and Jamaican workers,” Vlaar says. “He taught us that by example.”

Canada’s Agricultural Labour Laws Criticized by United Nations A brief history of workers’ rights in Ontario.

In an age when unions, strikes and back-to-work legislation make news every day, the legal plight of Ontario agricultural workers goes largely unnoticed.

Agriculture has always been treated differently than most other sectors. When the government passed the Collective Bargaining Act in 1943, agricultural workers were not included among the employees who received legal protection to unionize. Agricultural workers were also excluded in 1948 from protections under the Labour Relations Act.

In 2001, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that, by ignoring the association rights of agricultural workers, the Labour Relations Act was unconstitutional. The Government of Ontario was ordered to provide agricultural workers with the protections necessary for meaningful collective action.

On June 17, 2003, the Agricultural Employees Protection Act (AEPA) came into force. The legislation provides certain protections for organizing, but continues to exclude agricultural workers from the Labour Relations Act.

Later that year, the United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) and three agricultural workers complained that the AEPA offered insufficient protections and that continued exclusion from the Labour Relations Act was unconstitutional.

The application judge dismissed the complaint, but on May 20, 2008, having appealed the decision, UFCW presented their case to the Ontario Court of Appeal. The court found that the AEPA violated freedom of association, as protected by Section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The judge gave the Government of Ontario one year to determine how they would protect the collective bargaining rights of agricultural workers.

However, on April 29, 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada overturned the lower court’s decision, claiming that the Ontario Court of Appeal overstated the scope of collective bargaining rights.

Interestingly, five months earlier, the United Nations International Labour Organization (ILO) had criticised the Government of Canada and Ontario for violating the human rights of over 100,000 agricultural workers. The criticism came after the UFCW complained to the organization in March 2009.

On Nov. 23, 2010 during a meeting of the Ontario Legislature, in reference to the ILO criticism, Andrea Horwath (NDP, Hamilton Centre) asked why the government was “so hell-bent on denying basic human rights to the people who grow our food and help feed our families?”

“We do understand that the ILO has made some recommendations regarding collective bargaining within the agricultural sector,” replied Peter Fonseca, who was then the Minister of Labour. “However, as this case is before the courts, it would be inappropriate for me to comment.

“We’ve made great strides when it comes to the agricultural sector,” Fonseca continued. “We will continue to ensure that workers, in agriculture or in any other sector, are kept safe.” —MF

It Starts with a Conversation How churches can help.

“The situation of foreign workers in Canada differs greatly from place to place, from farm to farm, from community to community,” says Katharine Masterton, program coordinator with the national church’s Justice Ministries department. “I don’t think there is one answer. You can’t say that all churches should do this or that. The best approach is to just sit down and have a conversation.”

Nancy Howse, a member at St. Andrew’s, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., has been having that conversation since 1987 when she worked as a cashier in her local Virgil, Ont., grocery store. On Friday nights, when the workers drove in for a week’s supply of oil and rice, Howse would invite them to church and Sunday lunch.

“We were pretty ignorant in the beginning,” Howse recalls. “But as our family got to know a few workers as friends, they would share their stories with us.”

There are good stories and there are sad, frustrating stories, Howse says, but what all workers have in common are the daily challenges of living in a new country. Howse began spending more and more time driving her new friends to doctor’s appointments, picking them up for church and explaining numerous government forms.

In 1999, she joined the Caribbean Workers Outreach Program, a project of the Niagara presbytery that brings two Caribbean pastors to Canada each summer to minister to the migrant workers in the region.

“We need to take seriously our mandate to look after the stranger in our midst—to treat them as we would like to be treated,” Howse says. “If we step out of our comfort zones and actually meet them … we would be inspired by God to reach out in new ways.” —MF