In September 2011, Rev. Gordon Haynes, then the associate secretary of Canada Ministries, was assigned a “research project to provide a report for the Life and Mission Agency for its use in charting a way forward with vision and an enabling spirit for ministry. It will provide a realistic understanding of the challenges and offer recommendations to the LMA that each presbytery could take for further study

and the LMA can incorporate into future planning.”

The Haynes Report—The Life and Mission Agency Research Project 2011-2012—is cleanly and clearly written. It pulls no punches. It tells the harsh story of church decline and the Presbyterian Church in Canada’s inability to respond effectively to that decline over the decades. It is an honest report.

This is not the first such report to be done within the PCC. By Haynes’ own account, his completes a baker’s dozen over a half century. Perhaps this proves our running joke—which would be funny if not so true—that we love committees more than action. We didn’t get here suddenly; we watched it happen slowly over decades while we made notes and had lots of meetings.

Haynes’ task was to research the past, the demographic trends and think about the future of the church. He had an advisory group which helped him discern the information gathered. He filed the report a year later.

There is much to chew here and we hope you will add your voice to the discussion at the bottom of this article. —Andrew Faiz

Focusing On Our Hope

“Let us hold fast to the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who has promised is faithful. And let us provoke one another to love and good deeds.” (Hebrews 10:23-24)

I found that there were a variety of responses to the question of where the church will be in 10 years. Some who answered failed to see much hope, but I also found in my research and conversations many who both care for the PCC and have hope in its future. This hope is grounded in what they see God doing in their midst.

It is not clear yet what might emerge from these times of crisis, transition, and fear of failure. I have become convinced that change has to happen, and the issues facing us are complex. But I am confident that God will provide the opportunities and the people to redefine and revive God’s church yet again in this new context of post-Christendom secularity and spirituality.

Where will this redefinition and revival come from? One important conviction in this report is that the ground from which a renewed Presbyterianism will grow in Canada is the local congregation – those communities of disciples gathered week by week to be equipped for mission in their worlds. Jesus Christ and his people will endure.

This report will hopefully not shy away from the challenges and difficulties that confront the PCC, but will also recommend some steps that might make our hope more vital and energizing. I think this approach better reflects the enduring hope we have in the promise of the Gospel, and provides a good starting point for the emerging forms that God’s mission will take in this world.

SOCIETAL CHANGE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PCC

Factors

One thing that we know is that for about 150 years the way the church did ministry seemed to work well in Europe and North America. The church building sat as the centre of the church’s life, bringing people together for worship, fellowship, and assistance. From the early 19th Century until the middle of the 20th century, the church served as a centre of community life, and in that way supported, and was supported by, the cultural values around it.

However, in the middle part of the 20th Century, our society’s culture changed dramatically, demanding changes on how we as a church minister to others. But it would seem that our response to the change was to return to the fact that for 150 years our ways succeeded. We just needed to work harder, or do things better, but we would continue to do what had succeeded. The result was that we got left behind. This is not surprising, since (as is pointed out in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization by Peter Senge) previous success can be the biggest obstacle to change.

Why did our society’s culture change? There are a number of suggestions about the cause of the change.

Some have written that as we move from the Industrial Age to the Information Age, the level of disruption will be much like that when we moved from the Feudal Age to the Industrial Age, and we find ourselves presently on the cusp between these two ages – a very uncomfortable place to be.

Others, like Phyllis Tickle in The Great Emergence, see eras in the church’s life lasting about 500 years. The emergence of each era brought traumatic change to the church, but from each of them the church emerged, changed but strengthened. As she says in her book, “ … as Bishop Dyer observes, about every five hundred years the empowered structures of institutionalized Christianity, whatever they may be at that time, became an intolerable carapace that must be shattered in order that renewal and new growth may occur. When that mighty upheaval happens, history shows us, there are always at least three consistent results or corollary events.

“First, a new more vital form of Christianity does indeed emerge. Second, the organized expression of Christianity which up to then had been the dominant one is reconstituted into a more pure and less ossified expression of its former self. As a result of this usually energetic but rarely benign process, the Church actually ends up with two new creatures where once there had been only one. The third result is of equal, if not greater, significance, though. That is, every time the incrustations of an overly established Christianity have been broken open, the faith has spread – and been spread – dramatically into new geographic and demographic areas, thereby increasing exponentially the range and depth of Christianity’s reach as a result of its time of unease and distress.”

Still others see the changes in the worldview arising after the Second World War, and wonder if the occurrence of two world wars within a generation affected the parents of the Boomer Generation and beyond.

However we see the causes of the great changes in our society and the church over the last 50 years, we cannot escape the fact that major changes have taken place in attitudes about the church, and the church generally has been unable to adapt successfully to those changes. There are various factors in that change to which we have had to adapt.

One factor is that the makeup of our churches has changed (certainly in parts of Canada) because of the effect of multiculturalism on the Canadian landscape. Canada is today made up of people of many colours, cultures and religions, which mean further changes in how we interact with the society around us. That change in the makeup of our Canadian society also impacts the church. Our church has become more diverse. Much of the growth we have experienced over the last few years has been in the planting of congregations, and many of those congregations have been based on a common language or culture. Of course, there are an increasing number of congregations which contain a mixture of cultures, but the question is how we can integrate all this diversity into the whole of the PCC.

Another factor is the aging of the society. The Boomer generation is now reaching the point of becoming the Senior citizens in our society. This wave of people, who continue to impact the various parts of our society because of their relative numbers, also have an impact on the church. The average age of a member continues to go up, and more and more of those attending church services are senior citizens.

Impact on the PCC since the 1950’s

Peter Coutts and Stuart Macdonald wrote a paper as a part of the research for this report. Their historic and sociological overview of Presbyterian and Mainline Church decline is summarized in the first paragraph by this sentence:

“The trends are real and represent a new reality for the church as it continues its mission.”

I have included the entire paper in this report. Before I continue, let me add a number of caveats that have arisen during conversations about the findings:

1. The statistics used are from The Acts and Proceedings of the various General Assemblies. Since the statistics are self-reported, they may not be completely accurate (Communion Rolls have been known to be “inflated” at times), but the trends are over such a long period of time, they are (I believe) quite valid.

2. The picture painted by the statistics, and our projected scenario, is for the church as a whole. I personally know of churches that are doing really well, but those individual cases don’t change the overall picture.

3. While this report looks at the PCC, similar reports could (and have been) done about other denominations. This is not something that is unique to us.

4. The picture painted here is not complete if we only look at the statistics. We need to look at what is happening around us, how the church has reacted over the years, and ideas on how we can change in the future if we hope to have a whole and complete picture.

Decline in The Presbyterian Church in Canada

Summary:

Canadian society began in the 1950’s to experience what has become a dramatic shift in its culture, which has become a discontinuous change in our society. A significant consequence has been on Christian churches. After years of growth and vitality these Canadian denominations, in particular mainline denominations, began to experience numeric decline. This decline began in the late 1950’s when some parents of baby boomers chose not to participate in traditionally important family involvements in church: the baptism of their children, church school involvement, confirmation of teenagers, worship attendance and membership. This became a self-reinforcing trend which perpetuates a downward spiral of declining involvement by the subsequent emerging generations. These trends are real and represent a new reality for the church as it continues its mission.

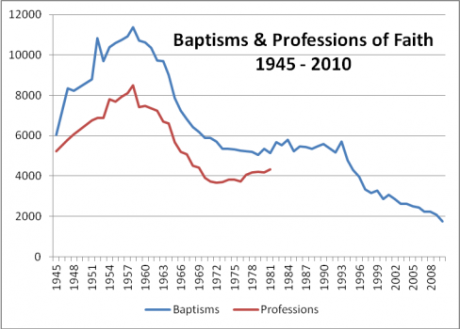

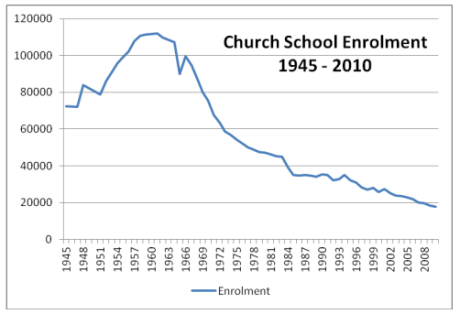

Observation #1:Children are losing the socializing influence of church involvement

After significant growth in the post-World War II period, baptisms and professions of faith both peaked in The Presbyterian Church in Canada in 1958, which is important to note. It was infants who were typically baptised and teenagers who were typically confirmed. This suggests that societal change in the late 1950’s affected both younger and older families equally. Both baptisms and professions subsequently saw dramatic parallel declines during the 1960’s, leveling out somewhat around 1973. Since 1993 the number of baptisms conducted annually began again to decline, and decline significantly, from 5,698 annually in the year 1993 to 1,749 annually by the year 2010. This represents a decline of 70% in the number of baptisms conducted annually over the past 17 years. Church school enrolment followed the trend for baptisms, peaking in 1961 three years after the baptism peak. This makes sense since children baptised in 1958 would be around four years old in 1961 and approaching their age eligibility for church school enrolment.

These three trends did not follow changes in Canadian demographics. Fewer Canadian children were being baptized in the later years of the baby boom, and this trend has only dramatically continued. This suggests that these changes were the consequence of choices made by families. It is important to stress that this experience of The Presbyterian Church in Canada was not unique. The United Church of Canada and the Anglican Church of Canada also experienced the same kinds of declines (For more on this, you can go to the working papers Brian Clarke and Stuart Macdonald prepared for the UCC and Anglicans).

As The Presbyterian Church began to recognize these changes, it initially assumed that responsibility lay internally with polity changes, such as changes in church school curricula and changes in new church development. But the primary cause for these declines rests with the new choices families were making. The Builder Generation—weaned on the values of duty, responsibility and conformity during the Depression and the Second World War—was expressing new values for their children. They were now promoting, permitting or condoning values for individualism and freedom of choice in greater ways in an atmosphere of growing permissiveness. This has grown more and more pervasive with each succeeding generation of parents. For example, in 1975, 23% of Canadian parents said that their children never attended church school (not even occasionally). By 2005 this figure had risen to 51%. Over the past fifty years the idea that religious belief and practice are matters of personal and private choice has become the cultural norm in our society.

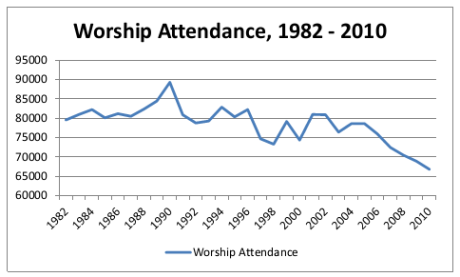

Observation #2: Each subsequent generation since the Builder Generation is less likely to be church involved compared to preceding generations

Worship attendance in The Presbyterian Church has only been monitored since 1982. This means we don’t have the statistics for the crucial years of the 1950’s and 1960’s. At the same time, we can look at more recent trends. Until 2005 worship attendance hovered around the 80,000 people mark. Since 2005, however, it has seen a very steady decline from 78,610 to 66,783 in 2010, which represents an average decline of 3% annually. Again other Canadian mainline denominations experienced similar declines in worship attendance.

There are three important observations to be made regarding changing worship habits in Canada. First, since the Builder Generation each subsequent generation has been less likely to attend worship compared to its immediate predecessor generation. Take, for example, how four age groups compare for non-attendance:

- For people over 65, non-attendance increased from 21% in 1985 to 25% in 2005

- For people age 45 to 64, non-attendance increased from 15% in 1985 to 33% in 2005

- For people age 25 to 44, non-attendance increased from 25% in 1985 to 36% in 2005

- For people age 15 to 24, non-attendance increased from 22% in 1985 to 33% in 2005.

In other words, the ranks of the disinterested are growing.

Second, regular worship attendance among the most faithful has been declining at the same time. The number of Canadians who attend worship “at least once a week” has declined for all age categories between 1985 and 2005:

- For people over 65, from 42 to 37%

- For people age 45 to 64, from 39 to 22%

- For people age 25 to 44, from 25 to 16%

- For people age 15 to 24, from 23 to 16%.

Where is this trend going? In 2008 47% of Canadian teenagers claimed that they had never attended a worship service ever in their life. This group is now emerging as Canada’s youngest adults.

One of the consequences of this is that Christianity is becoming de-institutionalized. People may, in Grace Davie’s phrase, believe without belonging. Today less than one-third of those Canadians who believe that Jesus is the Son of God actually attend church with any frequency at all. Since the 1950’s a growing number of Canadian Christians do not see worship attendance either as an obligation of their religion or as a personal need. Lifestyle changes have also had an impact. The most significant societal change in the past fifty years has been the dramatic increase in the number of working mothers, which has been suggested as the #1 reason for the decline in worship attendance among families. Families with two working parents now need the weekend for household management and family time. Family members over the past 50 years have also found more and more things to do with their time. Subsequently Sunday worship has declined over time as a priority activity for people’s discretionary time. Finally, since the Builder Generation people have not been inclined to be “joiners”. Past generations found great meaning through being members of organizations such as congregations. This is no longer the case, and organizations as diverse as Girl Guides, Scouts, CGIT, the Masons and congregations have all suffered equally from this cultural change. Cultural changes such as these have led to less involvement in church, and less involvement fosters declining meaning.

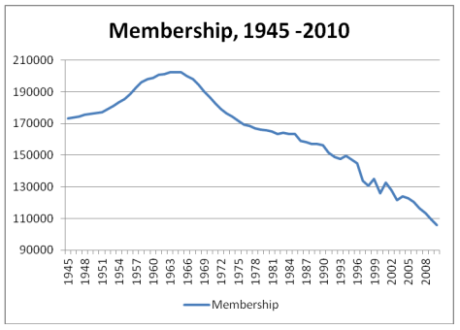

Another consequence of this is a declining number of active members. Membership grew steadily in the immediate post-War period. It began to decline in The Presbyterian Church in Canada after membership peaked in 1964. We can see two main sources for this continuing decline. The first has been the decline in generational replacement. Congregations are maintained over time when newcomers to congregations replace those who leave or die. Generations subsequent to the Builder Generation have been less and less inclined to become involved in church. This led to overall decline and an aging membership. A second source of membership decline has been through involved Presbyterians dropping out of involvement.

The demographic study conducted in 2000 found that the largest source of membership loss in that year was from Baby Boomers and Baby Busters / Generation X persons dropping out of involvement. After this the next source of loss was death. Again this led to both overall decline and an aging membership. Today the membership of The Presbyterian Church in Canada is half of what it was at its peak in 1964. The demographic study proposed that denominational demographics will be such in our current decade that death will become the most significant source of membership loss.

Dr. Reginald Bibby in his 2011 book summarizes things this way: “Don’t get me wrong. People are not yearning for churches and their counterparts. No one should trivialize what twenty-first century Canadians want by naively assuming that the findings tell us that most will “come back to church”. I’ve been reminding everyone for some time now that we have never found (italics his) anything in our research that points to the uninvolved being in the market for churches.”

Observation #3: Lack of participation in religion leads to the loss of meaning of religion

Religion is losing its meaning for Canadians, which can be illustrated in a few different ways. Within all generational groups the number of Canadians who “definitely” believe in God has declined over time. One question Dr. Reginald Bibby asks in his surveys is, “Do you definitely believe in God?” 66% of the Builder Generation said “yes” in 1985, but the number of definite believing Builders declined to 55% by 2005. For Boomers it was 55% in 1985, declining to 48% by 2005. For Baby Busters / Generation X in 1984 54% answered the question “definitely”, declining to 49% in 2005. In 2008 the “definitely” group of teens was only 37%. Not only is each successive generation less certain about the existence of God compared to its predecessor generation, but over time the certainty within each generation has also declined as well.

The 1991 census told us that there were about 400,000 Canadians who considered themselves Presbyterian who were neither members nor adherents of a Presbyterian congregation. By the 2001 census that number had declined to about 200,000. Over a ten year period a significant number of uninvolved Presbyterians recognized their reality and dropped the idea of being Presbyterian from their sense of identity. [The use of data from the 2001 census is because the data from the 2011 census is not yet available.]

The percentage of Canadians who have “no religion” is increasing. In 1951 and 1961 this was under 1% of Canadians, according to data from the Canadian census. By 1971 this had grown to 4% and continued to grow to 16% by 2001, when it was the second largest religious denomination in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, in 1985 32% of Canadians either had no religious affiliation or did have a religious affiliation but never attended worship. By 2004 that combined group grew to become half the Canadian population.

Observation #4: The loss of meaning of religion leads to secularization, which is the growing Canadian trend

Sociologist Dr. Steve Bruce (University of Aberdeen) has proposed the following mechanism for how secularization happens:

“The declining power of religion causes a decline in the number of religious people and the extent to which people are religious. As religious faith loses social power, it becomes harder for each generation to socialize its children in faith. It also becomes progressively harder for those who remain religious to preserve the cohesion and integrity of their particular belief system. As religion becomes increasingly a matter of free choice, it becomes harder to maintain boundaries. Alternative reworkings of once-dominant ideologies proliferate, and increasing variation encourages first relativism – all roads lead to God – and then indifference as it becomes harder to persuade people that there is special merit in any particular road.”

Historian Dr. Callum Brown (University of Dundee) argues that the secularization we see today is a new and growing cultural phenomenon which has its roots in the 1950’s and 1960’s. There is a growing awareness among British scholars that this represented a crucial turning point in the religious life of Britain and one can see the same trends occurring in Canada. Cultural changes since then have formed the building blocks for what really changed the face of Christianity in the West, which was what he calls the discourse revolution”. In essence, what people talked about regarding religion, and how free people felt in expressing their religion, changed. Religious practice became less public and families became less conversant about faith. Religion which is not communicated and demonstrated is not passed on. Children were no longer being socialized into Christianity through practices in the home and through church involvement. As Brown puts it, the generation which “came into adulthood in the 1970’s exhibited even more marked disaffiliation from church connection of any sort, and their children were raised in a domestic routine largely free from the intrusions of organized religion… The result has been that the generation that grew up in the sixties was more dissimilar to the generation of its parents than in any previous century… Of course, the new cultural environment affected the churches deeply, and transformed them fundamentally.” To put this into the language of post-modern philosophy, the Christian faith quickly ceased to be a meta-narrative for the culture.

The public presence of Christianity in society, as well as people’s personal involvement in a congregation and in personal faith practices helps keep people in what sociologist Dr. Peter Berger (Boston University) called a “plausibility structure”. Churches, traditional religious practices and the evidence of many participants in Christianity provide the evidence – “plausibility” – that the Christian belief is true. Societal change has provided less evidence, so people see Christianity as less plausible, which reduces the public presence of Christianity and the number of involved people, which means there is less apparent evidence, and so on. This has produced a self-reinforcing spiral which has removed Christianity from its central place in our culture to ever-more distant periphery in our culture.

Summary:

Canadian Christians, including Presbyterians, find themselves in a new situation. We have experienced several decades of decline in membership, involvement of young people (baptisms, Sunday school, professions of faith), and active participation at worship. This decline followed a period of significant growth and vitality. This has made the acceptance of this change much more difficult. At the same time, we need to accept it. The evidence is now fairly clear that this was driven largely by external forces, a culture change, which affected not only our denomination but all of Canadian society, and beyond that, most Western societies. Our challenge is to find ways in which we can engage this new reality.

RESPONSES OF THE PCC SINCE THE 1960’S

Since the 1960’s, the PCC has authorized, and received, numerous reports looking at the state of the church. I am not confident that this is a complete list (I keep finding others), but it is an impressive list even as it is:

- (1964) Ross Report (final report in 1970)

- (1969) Life and Missions Project (LAMP) Committee Report

- (1971) “Declining Church Membership”

- (1978) Special Report on the State of the Church

- (1980’s) Church Growth to Double in the 1980’s reports

- (1988-1992) Vision Statement and Strategic Planning

- (1994) Live the Vision final report

- (1995) State of the Church Report

- (1996-1997) Think Tank report

- (2000) Interim Report of the LMA

- (2001) Study Group to research denominational membership decline

- (2002-2011) Reports to General Assembly by the Long Range Planning Sub-Committee of the Assembly Council.

I have included in the appendix a summary of the recommendations of many of these reports (as amended or referred) as well as the reports themselves, but there are some things we can learn from these reports. As Peter Coutts wrote in a paper given to the LMA from its Future Direction’s Team in 2004,

“Our church finds its prime motivator to consider changes from a sense of impending or experienced “crisis”. The two major exceptions to this were the production and promotion of the VISION statement of 1989 and the development of the FLAMES initiative. Otherwise, our ventures into exploring current denominational realities and considering change has been prompted by pragmatic fears for the institution of the Church.”

The State of the Church Report (1995) whose recommendations were withdrawn by the committee after the response in the Briefing Groups at General Assembly, went further and said,

“For an entire generation people in our denomination have been declaring the same perceived needs while seeing little by way of change. What does this tell us? This is part of the explanation for why our people are losing interest in our denomination beyond our congregations. It illustrates that while we recognize our needs we have not yet taken them seriously enough to address them. It is clear from this overview that structurally we have an inability to change.”

However, we need to recognize that the various reports display a deep concern for the church, and each tries (from its own perspective) to give wise counsel to the church. There is a consistent unease that there is something that needs to change, and honest attempts to deal with that unease from different starting points. Some reports made recommendations that brought about changes still felt today – the emphasis in the early reports of involving women and youth in the decision-making parts of our church, for example. Others suggested changes to the structure, and even (in one report) suggested loosening the rules for a couple of years so that presbyteries and congregations could more easily “experiment” with new ways.

The reports were, to a great extent, responses to perceived crises facing the church.

- The mandate for the Board of Evangelism and Social Action, who reported in 1971, was, “That the General Assembly (the 94th ) appoint a special committee to study the problem of declining church membership with the instructions that it bring a comprehensive report to the 95th General Assembly with recommendations as to how this downward trend in the membership may be reversed.”

- The mandate for the report of the Boards of World Mission and Congregational Life in 1978 was, “This report is the result of a directive from the 102nd General Assembly to the Boards of World Mission and Congregational Life to ‘consider the serious relative and actual decline of the members of The resbyterian Church in Canada, the possible relative decline in income and other aspects of the church’s life … and to report on the state of the church with recommendations.’”

- Concerns mentioned in the final report on the Live the Vision campaign in 1994 led directly to the General Assembly forming the State of the Church Report Committee which reported in 1995.

- At the 1995 General Assembly, the Assembly Council recommended the creation of the Think Tank with the purpose of, “…examining and thinking through all the key factors which contribute to the position in which we find ourselves as The Presbyterian Church in Canada today, and coming up with a set of proposals that will enable our Church to set clear priorities and direction for the future.” The Think Tank’s reported in 1996 and its implementation committee reported in 1997. That year they said, “There was much

evidence in the replies to a great deal of conflict, confusion and pain within our denomination at all of its levels.” - At the 125th General Assembly, the Life and Mission Agency was asked, “…to convene a study group to research (1) the causes of congregational decline in the past 5 years, and (2) present proposals for the recovery of congregational health.” The Life and Mission Agency formed a Study Group to Research Denominational Membership Decline which first reported in 2001 with a denominational study analyzing membership changes as well as creating a tentative projection of future membership change.

Given that many of the reports were tied to feelings of concern about denominational decline in numbers, it should not be surprising that many of the recommendations made over the years were structural in nature. Over the years, there were suggestions for changes at each of the levels of governance in our church.

The Life and Missions Projects (LAMP) Committee Report, for example, recommended:

- a committee structure for Sessions, open Session meetings, and term eldership.

- that “Presbyteries be encouraged to experiment in new forms of mobile task-oriented congregations” and that all levels of courts be intentionally open to women and youth.

- that “… the Assembly designate the next five years as a time for study and experiment at all levels of church life (within the law of the church) in matters pertaining to church government and administration, Sessions and Presbyteries being encouraged to interpret the law of the church with as much openness and flexibility as the law allows”.

- that “… Presbyteries and Session be ready to report to the General Assembly (or an agency established for the purpose) whatever finding they may have from their study and experimentation.”

The LAMP Report was far reaching, touching on Theological Education, Continuing Education, and ministry to French-speaking peoples. It is interesting to note that most recommendations (32 in all) were adopted, with the rest adopted as amended.

As an aside, this seems to be a relatively constant part of these reports. The recommendations are either adopted (although whether they all are acted on is another question), or amended (often after being softened, or referred to some committee or board for study). Very few were actually defeated although, as mentioned before, the recommendations of the 1995 Report on the State of the Church were withdrawn by the committee. Also, the final paragraph of the 1971 report was erased from the report – there is actually an open space in the Acts and Proceedings (The erased paragraph is included in the appendices). However, as one reads the reports and their recommendations, it becomes clear that while the recommendations were (in the majority) adopted, not much action came from them.

Peter Coutts, in a paper “An Historical Overview of Past State of the Church Reports”, summarizes the common points from many/all of the reports:

- The origins of the study and/or report were impelled by a perception of “crisis” which had to do with pragmatic, institutional issues such as membership decline and income being less than expected.

- The need for congregational renewal and health is a major theme of the report.

- Youth/young adult involvement in church life is seen as critical.

- The need to improve vitality in fostering meaningful worship.

- Religious leaders are “out of touch”, or congregations need to be relevant to the times.

- Members feel remote from the courts of the Church.

- Survival mentality in congregations is prevalent.

- Congregations are not pro-active enough to reflect on program needs and its mission focus.

- We are hesitant to talk about our faith and do evangelism.

- There is a lack of clear understanding of our national purpose and mission as a denomination. After the Vision statement of 1989, the emphasis shifts to the need for presbyteries and congregations to develop clear purpose and mission understandings locally.

- The Church is slow to respond to issues at times.

- The report proposes a restructuring of the national organization/staff as a needed response to the current reality.

- Clergy do not get sufficient training in the practical elements of ministry, or need to be trained to fulfil the current priorities for congregational life.

- The confrontational style of decision-making used in church courts must be improved.

- Areas of change must be explored with the grassroots before changes are implemented.

These points came from reports spread over a period of about 40 years, meaning that the authors of the various reports saw the same, or similar, issues continuing to face the church. It is no wonder, then, that the authors of the 1995 State of the Church Report concluded their report saying,“Given our denomination’s past experience of trying to bring change bureaucratically and ‘top down’ we frankly remain unconvinced that anything we recommend would ultimately make any difference.”

Current state of the PCC

The decline documented above has affected the church in a number of different ways, beyond the obvious of there being fewer, smaller congregations, and less available resources.

There has been a level of denial about the reality of the decline or the need for change. For example, I have had members of presbyteries tell me that there isn’t an issue around decline – that congregations across Canada have just all decided to purge their rolls at the same time. Others have pointed me to specific congregations in their area which are growing as evidence defeating any discussion of a general decline.

This leads to the danger that we will try to maintain everything that we have done in the past, which in turn means that the PCC risks living beyond its means – paying for programs and structures that are no long needed out of monies saved over time.

With others, there has been a sense that we are the last generation. In the last few years of my time with Canada Ministries, I noted that presbyteries seemed less and less willing to take risks starting new congregations. I occasionally made reference to that feeling as a kind of “Ecclesiastical Depression” – a term that I agree is an overstatement of what I experienced. However, in talking with the members of my Advisory Group, others shared that they had felt a similar feeling in their own presbyteries or in the presbyteries around them.

My Advisory Group described this feeling as “despairing lethargy”. It is the realization that the

Church is getting smaller, and a despair that there seems to be nothing that can be done about it, that leads to a general lethargy about trying new things. This feeling in turn leads to a decreased capacity to change, and a reliance on the inherited models of the church that have worked in the past.

In presbyteries, it seems that there may be a minority who work toward a new way of doing things and seem to have the energy, but our “despairing lethargy” is present among the majority. No one has time or energy to tackle things. How do we create the space for conversation so as to hear the Holy Spirit move us? People know that they have to change, but they don’t know how to learn to be different.

The Advisory Group also noted that in congregations, many people do not know how to use the language of faith. We hear a lot from people who want to keep the institution going, and this becomes their goal rather than developing a community of faith. Increasingly our congregations are filled with those of the zoomer/boomer/retired generations. How do we help this group speak of their faith to their children and grandchildren?

A SCENARIO FOR 2020

So, given the cultural change that is going on around us, and the church’s failure over the last 50 years to adapt to the new culture, what will our denomination look like by 2020? At the discussions I held with presbyteries, some noted that we cannot forecast where the Holy Spirit will lead the church. That is true. However, we can look at where the institution of the church has gone over the last 40 or so years, and (from that past and present performance) express some expectations of what the church will look like in 10 years.

The assumptions we have used in this scenario:

- We will see the changes happening in our society become deeper, so the impact of the changing culture on our society and our denomination will become stronger.

- We can realistically anticipate that the decline in the PCC will continue at an accelerated rate, given societal change and our current demographics.

According to the statistics in the Acts and Proceedings, the PCC had around 204,000 members in 1964. By 2010, that was down to 105,886 – a net decrease from the year before of 3,537. The assumptions mentioned above being taken into account, if we continue as we have without major changes, we see a scenario where the PCC will have (according to our own figures) around 65,000 members in 2020. That is about 2/3 the size of the church in 2010. Because of the age of members in our congregations, we would see there being a similar decline of about 1/3 in our number of congregations (meaning just over 600 congregations) and a decline of 40 to 50% in what is given to Presbyterians Sharing.

Some reading this report may dismiss this forecast as either unsubstantial or alarmist. However, we would make these observations. First, over the past four decades the rate of membership decline has been steadily increasing. Second, we are able to anticipate in the near future a sharp increase in the rate of membership decline given the significant number of congregants who are in their 70’s or 80’s and the current average Canadian life expectancy is 80.7 years. Finally there is no indication that the direction of the cultural trends of our society are changing, which means societal culture will continue to have a significant – and growing – impact on our future.

It is sobering to imagine the impact this degree of membership loss will have on congregations as well as the impact this number of congregational closures will have on presbyteries. At both these levels we will see an increase in the sense of organizational and financial strain, and thus growing stress. The coping capacity of congregations and presbyteries will be challenged. However, these challenges will also motivate many congregations and presbyteries to imagine new ways of being. This gives us hope.

For the LMA the impact of this decline will have two consequences. First, it will change the kind

of ministry the LMA has to congregations and presbyteries. It will have two emerging priority

roles:

- To provide resources and support for congregations and presbyteries as they deal with the organizational and financial strain.

- To act as a midwife assisting the birth of a new kind of Presbyterian Church which will emerge at the grassroots level of congregations and presbyteries.

The second impact of decline will be the reduction of the financial resources available to the LMA to deliver this changing ministry. Congregations under financial stress are forced to reset financial priorities, and when push-comes-to-shove Presbyterians Sharing is frequently – and usually reluctantly – pushed down the list of priorities. This is illustrated by comparing the change in total congregational income to congregational support of Presbyterians Sharing in recent years. Between 1996 and 2006 total congregational income increased 44% while congregational support for Presbyterians Sharing increased only 3.6% over the same period. Support for Presbyterians Sharing plateaued between 2002 and 2006, and since then it has been declining. Between 2006 and 2011 it has decreased an average of 1.7% annually. Over the coming decade we can anticipate that the annual decreases in congregational support for Presbyterians Sharing will grow disproportionately as compared to membership decline because congregations – as is their habit – will give priority to the maintenance of the status quo of congregational life.

What if we make changes? We would expect that we will still see a smaller church in the future. The difference will be that the decline may not be as great, and we would at least be a church better able to minister to the changing culture around us.

RESPONDING TO CHANGE

Looking at the scenario presented above, and the statistics underlying it, there is a very real possibility that we can get bogged down in our current reality. In fact, that is what has been seen presently through the denial and lethargy that is present. We are too prone to get caught up in the needs of the organization – the institutional church – and give priority to our desire to keep our current organizations going without giving greater priority to our calling in faith. This can, with time, lead to a loss of confidence that God is with us and for us. And yet, that is counter to our understanding of the Gospel. We need to remember the promises Christ made about his church, and regain (as the church) our confidence in the Gospel and its ability to speak to our culture.

Before I move further into responding to change, let’s take a moment and look back at a couple of points that have already been made.

- The decline is tied to a shift in culture in North America and the church’s failure to respond. While we have not helped by failing to adapt to the shift, the decline is not directly tied to our doctrine, or our music, or anything having to do with being Presbyterian. The same decline is found in our sister denominations across Canada and the United States. Indeed, in the September 2011 edition of Presbyterians Today, Jack Marcum (coordinator of Research Services of the General Assembly Mission Council of the Presbyterian Church (USA writing an article on “Where have all the children gone?”)

says “Having endured 45 straight years of net membership losses, perhaps Presbyterians have grown inured to the steady drip, drip, drip of declines. If so, it’s time to take notice. The findings presented here are the most sobering I’ve seen in more than two decades studying the PC(USA).” - We also have to remember that, as a church, we have not sat quietly during the years. We have looked at the state of the church a number of times. Our weakness has been that we emphasized the structure of the church in many of those studies, and we often haven’t carried through on the suggestions. It is not that we haven’t done anything – we just haven’t done nearly enough.

As I discussed this with my Advisory Group, it became clear that various issues needed to be addressed as we responded to the societal changes going on around us. The church’s culture needs to change at all these levels.

- As already mentioned, we need to regain our confidence in the Gospel. This is the centre of our belief.

- We need to focus our calling and goal on being missional in all that we do. This is our calling and goal.

- Evangelism is an important part of what we do. Put plainly, Churches need to become better evidence for God in our society. This means that we need to do a better job of faith formation both for newcomers and established members, helping people to be able to integrate faith into life and then articulate it.

- Our style has to be one of experimenting and entrepreneurial/adaptive behavior. The emerging church arises from experimentation. As a church we are too often afraid of failure. We need to be willing to give permission to fail. In his book, The World is Flat, Thomas L. Friedman quotes Michael Hammer saying,

“One thing that tells me a company is in trouble is when they tell me how good they were in the past. Same with countries. You don’t want to forget your identity. I am glad you were great in the fourteenth century, but that was then and this is now. When memories exceed dreams, the end is near. The hallmark of a truly successful organization is the willingness to abandon what made it successful and start fresh.” - We need to recognize what makes the PCC different from other denominations, and how we want to be seen as different. If we can no longer be all things to all people, what do we want to be and do well?

- Primarily at the congregational level, we need to give support for this faith nurturing and faith formation. We may need to build more of an educational component into our sermons, engaging people in the content.

- Coming to faith is a process, and is not a one event occasion. This means we need to help people mark this path and their moments on it. We need to discover the real deep meaning of Baptism, and reaffirm their Baptism on occasions later in life.

- We need to be more involved in investing in congregations than propping them up.

- In all that we do, we need to be authentic, prophetic, and pioneering.

Needs of Presbyteries

Over a couple of months earlier in 2012, I had the opportunity to meet with a majority of the presbyteries in our church to discuss what they saw in the future, and to hear what needs they could identify for them to continue to function in that future. Some of those meetings were in “roundtable groups” made up of a number of presbyteries together. Others were meetings with a single presbytery at a time.

At those meetings, I asked them what they saw God calling them to be, what barriers they saw to achieving those goals, and what was needed by them to overcome those barriers. As well, a number of presbyteries sent in reports on their discussions on the questions that were asked. As well, one presbytery reported that they had actually been doing a similar study for the past year, and sent me a copy of their findings. I have included a listing of their answers to all the questions, but I want to concentrate here on what they saw themselves needing from the national church (and particularly the LMA, or its successor).

I have tried to put their responses into a number of categories. First, I will address what they identify as needs, and then I will look at what suggestions they made as to what is needed to make this happen.

Resources

Educational material and resources that are user friendly. This would include online resources, and would touch on topics such as:

- Events such as Stewards by Design and the Emmaus Project.

- Preserving “sacred space”.

- Clustering/amalgamations/closing.

- “Clergy Care” stuff – a number commended this.

- Vital/healthy/real communities in spite of size.

- Things that are going well.

Resource people/staff who are familiar with and understand the local situation and context. These would be facilitators skilled in leading congregations through proven processes that produce change in people’s attitudes and the direction the congregation is heading.

Financial help, through money for new projects.

Training

Training in a number of areas for congregations and presbyteries:

- Relevant leadership training.

- Cross-cultural training.

- Training laypeople to take a lead – or participate in leadership – at worship.

There was also some discussion in most meetings on changing the training of clergy – to make them more available (this came from what could be described as rural presbyteries), better equipped to minister in the context to which they had been called, and to open up the possibility of alternative forms of ministry, such as tent-making ministries.

Leadership

This was different than training leadership (mentioned above under Training). It was for leadership itself. The wish was for “people who think outside the box,” and developing priorities on what to focus on.

Evangelism and Church Growth

Requests were for instruction on how to approach others (evangelism), and starting new churches.

New ways to do ministry

There were a number of requests for models of new ways to do ministry:

- Ministry without buildings.

- Tent-making ministries.

There was also a request for revisioning of the church and to look at alternate ways of doing ministry.

Structures

A number of suggestions came up here. Although they came from felt needs, they were more specific suggestions. I am putting all of them here so that you might get a sense of the feelings of the participants:

Some of the suggestions are generally for the LMA:

- Put more money into regional staff rather than national.

- Keep us connected to national committees (to be corresponding member of the committee isolates us from the church as a whole).

- Less administrators and more visionary leadership.

- Require each presbytery to make/remake a ministry (vital communities) with resources provided from LMA.

- Help presbyteries to change.

- Twinning strong congregations with churches needing leadership or other resources.

Some seem to be suggestions for the church as a whole:

- Revise structures and polity.

- We don’t have good mechanisms to create partnerships with other denominations or institutions. We have lots of rules that prevent it from happening. You almost have to leave the PCC in order to experience partnerships.

- Release the churches so that they can do innovative ministry.

- Abolish Synod.

- Give Presbyteries permission to encourage growth/health/vision, and presbyteries to give permission to congregations to have vision.

- Encourage the use of terms for elders and board members.

- Hold a General Assembly for Renewal.

- Give permission to use the Book of Forms as “guidelines” – more flexibility.

- Hold alternating General Assemblies – one year be business, the next concentrating on spirituality.

- Gathering together not so much for business, but for prayer, scripture study, celebration, support, etc. A holy fair?

Theological Training

There were requests for changes to be made to theological education. New models of theological education were to be considered – along with new models of congregational missions.

Best Practices

The sharing of best practices was mentioned. It was said that we can learn from the best practices in congregations – what is their ethos, their mission, their ministries and their processes? We should share what has been used in other areas and churches, to be inspired and educated by them. This would give encouragement of visioning different models.

Priorities

- The church needs to be missional.

- There needs to be a national priority for a ministry to seniors.

- Comforting those congregations that are sick.

- Rural churches need to be seen as being as important as urban churches.

It should be noted that a number of these expressions of priority are really cries for help from people who are saying, “WE should be a priority.”

Communication

A number of themes arose in this area:

- We need to communicate the vision, mission, and spiritual direction of the national church.

- The national church needs to listen to what is happening in the congregations and presbyteries.

- The need to tell our history.

There was also some advice for the national church:

- There is a need to move from a “plan and push” perspective of top-down resourcing to discovering what is emerging and evolving, providing astute support, and then sharing this so we can all benefit.

- “Get out of head office and into the churches”.

- The church needs to be prepared for a radically different form of Presbyterianism

Others

There were a few other needs suggested that may not fit easily into any of the above categories, but were considered important by those who presented them:

- We need to see decline as an opportunity that might push us into risky, but necessary, partnerships.

- Remember that our ultimate loyalty is to Christ, and our ultimate hope is in Him.

- See who God has contributed, even in small/closing congregations.

- The importance of prayer.

- Will the LMA even exist in 10 years?

What is needed to make this happen?

Out of this large number of comments by presbyters across Canada, there seems to be a few common elements:

- There needs to be more resources closer to the front line. Whether it is sharing “best practices”, or having regional people available to help, there was a general feeling that the resources had to be more immediately available, and under some level of control by those who used them.

- Our church has its share of conflict, which seems to show up in many different ways in congregations and presbyteries. I have heard from presbytery after presbytery that it is close to paralysis because of conflicts that have gotten bigger and bigger. At all levels, we need to learn how to handle conflict so as to bring about the best possible outcomes.

- The issue of changes in the training of clergy came up time and time again. This usually was in terms of “practical” training in things like leadership, conflict management, etc.

One further point needs to be made. During the conversations I had with the presbyteries, it was mentioned by four of them that they questioned if they would even continue to exist in 10 years. Others talked about being much smaller than they are presently. Concern for the future is present all the time. We may be hesitant to change our structures, but we need to understand that the structure of our church is going to change in the near future, whether we do anything about it or not. We need to prepare ourselves for those changes, so that we are able to continue to live out our faith in a changing world.

LEADERSHIP IN A TIME OF CHANGE

The question of leadership is important throughout the church. It is therefore not surprising that leadership came up in almost all of the conversations I have had over the last few months. Leadership is seen as being even more important as we face a future (and a church) full of change.

And yet, it was generally felt that we don’t place our hopes and goals high enough. We often

focus on keeping what we already have alive, or keeping our congregation open. We do this

rather than what best witnesses to Christ in an area, or for the sake of the congregation that

follows us.

While creative leadership throughout the church needs to be encouraged and developed, one particular area of concentration should be helping our clergy further develop skills in leadership, first through leadership training becoming part of the curriculum in seminary, and then through opportunities for continuing education. Perhaps we need to make upgrading of leadership skills though Continuing Education compulsory. The greatest leverage point that the national level of the PCC has in influencing change is the training of our clergy in our theological colleges, and post-graduation education.

It was the feeling of the Advisory Committee that presbyteries need to take more ownership of their responsibility to oversee education of students for the ministry – especially those looking towards the examination for certification for ordination.

Beyond the matter of training, it was felt that the church needs to encourage candidates who are more adaptive and entrepreneurial. We need to accept the risk that is associated with this, because one of the realities of entrepreneurs is how frequently they fail. As well, once they are in the field, the church needs to provide support so that they do not burn out or leave the ministry.