These congregations are becoming multicultural, with the minister and family from one cultural background (a minority culture in the community) and the rest of the congregation from other cultures (the majority cultures in the community). This contextual shift is not easy for the minister (and their family) or for the congregations.

One of the most obvious issues, and the one I hear raised most often, is that of language skills and accents. At a gathering of Korean Presbyterian clergy serving Caucasian congregations, I heard a good response to this. “When Canadian missionaries came to Korea, they preached the gospel in Korean. Their grammar was not perfect, their accents were hard to understand, but our ancestors heard the gospel and believed. Our English is better than the Korean spoken by the missionaries. People will hear the good news of the gospel and believe when we preach.”

A further question deserves to be asked: why would non-Caucasians go to serve these churches? Two factors are at play.

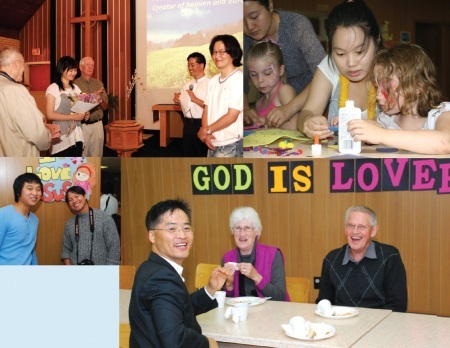

St. Andrew’s, Swift Current, Sask.:

Top: Rev. Jonathan Kwon and elders welcome new members; teachers help students with crafts at Vacation Bible School.

Bottom: Two of the church’s members; Rev. Kwon and two members enjoy fellowship time after a worship service.

First, just as there are doctors and engineers coming to Canada as refugees and immigrants looking for work in their occupational fields, there are Presbyterian clergy in the same situation. For whatever reason, no congregations within their language or ethnic group are looking for clergy, so the ministers seek calls in Caucasian churches. In economic terms it is an issue of supply and demand.

A second, deeper reality is also at play. Many non-Caucasian Christians, Koreans and Taiwanese in particular, feel indebted to European and North American churches for sending missionaries to their ancestors to proclaim the gospel. To repay the debt they become missionaries to parts of the world where the church is not doing well—Europe and North America. Canada is seen as a mission field to be reached with the good news of Jesus. Missionary outreach is deeply embedded in the DNA of the Korean church and Presbyterian congregations on the Canadian prairies are benefiting from that commitment to mission.

Whether the migrations of people are caused by political, social and economic transitions, or through missionaries intentionally coming to Canada, the missionary rebound is having an impact. The rebound is evident in Anglican, Lutheran and United churches as well, but nowhere is it more obvious than in Roman Catholic parishes. For example, in the Archdiocese of Winnipeg about a third of parish priests are first generation arrivals to Canada.

There are numerous challenges and opportunities presented to Caucasian congregations calling non-Caucasian pastors. It would be naïve to assume such calls are without risks and always have a positive outcome. Sometimes congregations do not thrive with a first generation immigrant minister leading them. But the same can be said about Caucasian clergy leading Caucasian congregations—not all congregations thrive. Yet, when lay people in these congregations were asked if they would have concerns about calling another non-Caucasian minister in the future, the vast majority said they would have no such hesitation if the opportunity presented itself.

Congregational life and ministry were described as being enhanced. Congregation members talked about how hard their ministers worked: launching new initiatives, working with groups in the church, reaching out to the community, and visiting in people’s homes. While not always explicitly stated, the clear implication was that first generation clergy worked harder than Caucasian clergy. Such a finding is not surprising since first generation immigrants, regardless of their occupation, are recognized as being hardworking. Moving to a new country requires significant personal initiative; therefore many immigrants are high drive people. That drive shows up in the plans and projects the first generation immigrant minister undertakes.

Other hard work is less obvious. When they first arrive in their congregation, ministers often write sermons in their first language then translate them into English, adding substantial time to their sermon preparation. Sometimes these ministers give their English sermon text to a native English speaker to read and correct. During some of my conversations with clergy, I was asked to explain some English idiom I had used. At first I thought the requests were so my hearer could understand what I had said; I came to realize often the ministers were seeking to improve their grasp of English by learning idioms, not just vocabulary and grammar. Lay leaders recognized the work the ministers put into understanding their new context. Living cross-culturally takes energy and commitment.