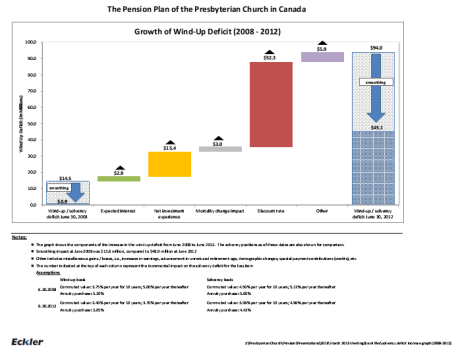

Faced with a $45-million deficit in the church’s pension fund, the Pension and Benefits Board is exploring options for how best to deal with the liabilities.

The shortfall has grown from $900,000 in 2008 to $45 million in 2012, primarily because interest rates have stayed at historic lows.

A fund’s liabilities are the benefits that have been promised to employees and retirees versus its assets, which are its investment returns or how much money is invested in the fund.

Some Definitions

In a defined benefit plan, members are promised a monthly benefit when they retire that is based on how much they earned and how many years they served—not on the fund’s investment returns.

Assets are the fund’s investments. Liabilities are the costs of providing pension benefits to members now and in the future.

If the assets are greater than the liabilities, the plan has a surplus. If, on the other hand, the liabilities are greater than the assets, the plan has a deficit.

A solvency valuation assumes a pension plan will wind up abruptly on a given day. It determines whether or not a plan’s assets would be sufficient to provide an immediate payout of the benefits members have earned.

A going concern valuation assumes a pension plan will continue to operate indefinitely. It determines whether or not the plan’s assets will be able to provide pensions for members in the years to come.

Because solvency and going concern valuations look at the same pension plan in different ways, it is possible to have a going concern surplus and a solvency deficit, for example.

When a fund is evaluated, actuaries determine whether if it were to wrap up abruptly on a given day, it would be able to provide all members with their pension benefits in a single lump payout. This is called solvency funding.Assets are the fund’s investments. Liabilities are the costs of providing pension benefits to members now and in the future.

If the assets are greater than the liabilities, the plan has a surplus. If, on the other hand, the liabilities are greater than the assets, the plan has a deficit.

A solvency valuation assumes a pension plan will wind up abruptly on a given day. It determines whether or not a plan’s assets would be sufficient to provide an immediate payout of the benefits members have earned.

A going concern valuation assumes a pension plan will continue to operate indefinitely. It determines whether or not the plan’s assets will be able to provide pensions for members in the years to come.

Because solvency and going concern valuations look at the same pension plan in different ways, it is possible to have a going concern surplus and a solvency deficit, for example.

Most single employer defined benefit plans, like the one the church has, have “significant solvency shortfalls,” said Hugh O’Reilly, head of the pension benefits and insolvency practice at the Toronto law firm Cavalluzzo Hayes Shilton McIntyre and Cornish LLP.

“Solvency funding is extremely sensitive to interest rates,” he said. “So what’s happened is, certainly for about the last 15 years and since the financial meltdown [in 2008], there’s been extraordinary pressure on 30-year bond rates. They’ve gone down. As bond rates go down, the value of the liabilities go up. And what that does is it creates the solvency deficiency.”

To fund its solvency deficit, the church would need to find an additional $400,000 a month or $4.8 million a year for 10 years starting in the first quarter of 2014.

Yet funding the deficit with additional cash payments may not be the best course of action, said Stephen Roche, the church’s chief financial officer. If interest rates go up in the future, the deficit will shrink.

Going Concern Funding

Pension funds must ensure they can provide current and future pensions to members as the plan continues to operate. This is known as going concern funding.

The church’s plan had a going concern deficit of $7.1 million in 2012. That was an improvement from a $10 million deficit in 2011.

Stephen Roche said increases to the mandatory contributions made by ministers and churches, as well as other church employers and employees, “are going a long way” to address the going concern deficit. The increases took effect in January.

Additional donations or bequests from members of the church could also “really help us,” said Tom Fischer, convener of the pension board. “Independent funding coming through the door could certainly do nothing but help the pension plan itself.”

The church’s plan had a going concern deficit of $7.1 million in 2012. That was an improvement from a $10 million deficit in 2011.

Stephen Roche said increases to the mandatory contributions made by ministers and churches, as well as other church employers and employees, “are going a long way” to address the going concern deficit. The increases took effect in January.

Additional donations or bequests from members of the church could also “really help us,” said Tom Fischer, convener of the pension board. “Independent funding coming through the door could certainly do nothing but help the pension plan itself.”

“Let’s say we scoured the church for $60 or $70 million and we put it into the pension plan; and then in four years we find out we have a $20-million surplus [because interest rates have increased and the solvency deficit has shrunk as a result],” explained Roche. “That didn’t serve the church well.”

“You just can’t take money out of the pension plan,” he said, noting there are regulations in place for dealing with surpluses.

Instead of funding the deficit with special payments, the pension board is considering using letters of credit to cover the shortfall in the short- to medium-term.

A letter of credit is a guarantee from a bank or financial institution—usually underwritten by a pledge of assets on the part of the organization seeking to secure the letters of credit—that, in the event of a bankruptcy or sudden wind-up, it would provide the amount of money that has been stipulated.

Banks charge a fee for the letters of credit they issue. Legally, this fee cannot be covered by the funds in the pension plan, so the church must find the money for the fee elsewhere.

“Four hundred thousand dollars a month is $4.8 million a year. That’s what you’d have to pay into the pension plan to cover the solvency deficit,” said Roche. “If I take a letter of credit for that $4.8 million and it’s at one per cent, that’s $48,000 [a year]. Instead of paying $4.8 million I paid $48,000, waiting for when interest rates go up and the problem becomes much more manageable. And then what we’d be able to do is slowly surrender those letters of credit.”

The pension board plans to seek approval from the General Assembly, which will meet from May 31 to June 3, to negotiate letters of credit.

The board does not believe the church can go bankrupt suddenly and therefore, the board argues, it should be exempt from solvency funding requirements.

“The windup calculation is artificial because the Presbyterian Church cannot simply go bankrupt in a day or a month or a year,” said Roche. “In essence the Presbyterian Church has assets which far exceed any pension deficit if we went bankrupt.”

The funds that appear on the national church’s balance sheet are only “the tip of the iceberg,” he said. The church’s total assets include the buildings and funds managed by the congregations across the country.

“If you were to take the balance sheet of all the assets of the church, it’s massive. If we’re one employer, which we are, then the coverage of this if we go bankrupt is not going to be a problem.”

The board is exploring possible ways to restructure the plan and then petition the government of Ontario, where the plan is registered, to exempt it from solvency funding requirements. This could prove to be a multi-year process, the board said.

At press time, the board was looking into what would be required to create a jointly sponsored pension plan. In a JSPP, employers and employees share governance and risk. This type of plan would be governed by 50 per cent employers and 50 per cent employees; employers and employees would each contribute 50 per cent of the plan’s funds; and, if there was a deficit, each group would be responsible for half.

Mature Pension Plan

The church has a mature pension plan, which means the number of members nearing retirement is much greater than the number of younger members.

“If we were back in the ‘60s, we’d have a lot of younger ministers coming in and we’d have what’s called a younger plan,” Stephen Roche told the Assembly Council. “Now we have a mature plan and we don’t have a lot of money coming in. That’s why we rely on interest.”

As this graph shows, there are currently more people drawing pensions from the plan than employees paying into it.

“The maturity of the plan doesn’t affect the deficit,”

Roche said in an interview.

“The maturity of the plan affects what’s called sustainability.”

“If we were back in the ‘60s, we’d have a lot of younger ministers coming in and we’d have what’s called a younger plan,” Stephen Roche told the Assembly Council. “Now we have a mature plan and we don’t have a lot of money coming in. That’s why we rely on interest.”

As this graph shows, there are currently more people drawing pensions from the plan than employees paying into it.

“The maturity of the plan doesn’t affect the deficit,”

Roche said in an interview.

“The maturity of the plan affects what’s called sustainability.”

“You’ll see other pension plans looking at 50/50 risk models as well because it seems to be something that is affordable, and so I’m imagining there are all sorts of hybrid solutions for specific plans,” said Judy Haas, the board’s senior administrator.

The board is in the early stages of its investigation and are working out how a JSPP might work in the context of the church. They may bring recommendations regarding a JSPP or another type of plan in the future, if they decide it is a wise course to take.

“It’s a tricky walk that we make,” said Tom Fischer, convener of the pension board. “There are a number of factors working here as we move forward to determine what we can be and what we should be.”