Have you ever been to a worship service that made you uncomfortable? Most of us would probably answer, “yes.” That’s because most of us have preferred ways to worship. But difficulties can arise when we think our preferred way of worship is the only way to worship.

At General Assembly this year, I led commissioners through an experiment. In his book, Gospel – Centered Spirituality: An Introduction to Our Spiritual Journey, Allan Sager argues that throughout the history of the church, Christian spirituality has been expressed in four main ways.

So I provided everyone with a series of statements to help them figure out which of those four spiritual styles best describes them. Then I had them repeat the process, this time focusing on the spiritual styles of their congregations.

I pointed to each of the four corners of the room and named off each of the four spiritual quadrants. I asked commissioners to go to the corner that represented their congregation’s preferred spiritual style. The vast majority flowed toward the area representing quadrant one—a spirituality of the mind.

Then I asked them to go to the corner that represented their own preferred quadrant. Laughter ensued as many left the first quadrant for other corners of the room. (Interestingly, very few flocked to quadrant four.)

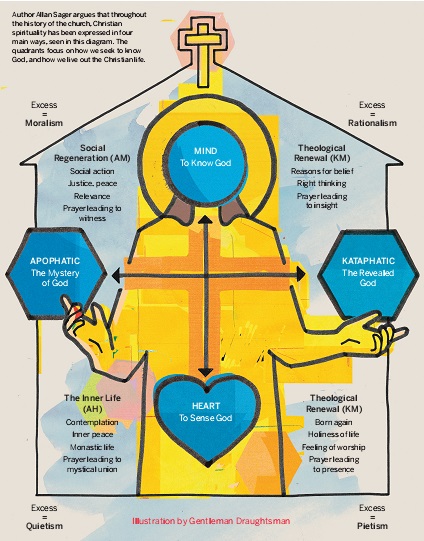

As seen in the diagram (See Below), the vertical line represents the ways in which we seek to know God. One end emphasizes knowing God intellectually and the other end focuses on sensing God intuitively. The horizontal line represents how we live out the Christian life, one end emphasizing God as revealed and the other end emphasizing the mystery of God.

The intersection of these two lines creates four quadrants that express the Christian life in different but equally important ways. If taken to an extreme, each quadrant has a negative side. Understanding these quadrants not only helps us to understand our own preferred ways of living out the Christian life including styles of worship, but can help us appreciate the preferred ways of others.

Quadrant One: A Spirituality of the Mind

This quadrant (upper right) represents those whose primary way of knowing God is through the use of the intellect. Here the goal is to understand things as opposed to changing them.

The Christian faith is expressed through words, concepts and images. Content is important and people here tend to seek guidance from scripture and sermons (i.e. from words) rather than a spiritual director, for example.

Worship centres primarily on gathering and the spoken word. Better sermons and more study groups are emphasized.

This quadrant seeks not only to experience God but to make sense of that experience. People look for those insights that help them fulfill their vocation in life. Theological reflection and renewal is important.

Prayer is largely word based. Hymns tend to be third person, speaking about God rather than speaking to God. The liturgy is well – ordered (rational).

There is less focus on personal piety or inner reflection and more focus on what Christ has done on the cross. Personal transformation is not so much about what I do, but what God does in and through the renewing work of the Holy Spirit.

This quadrant makes several contributions to Christian spirituality. It challenges the church to think through what it believes; it helps us make sense of our experience of God; it is committed to handing down the “faith” from one generation to another; and it seeks ongoing theological renewal.

However, when taken to an extreme it becomes rigid, dogmatic and routine, with an exaggerated concern for right thinking. There is an over – intellectualization of the spiritual life in a way that can rob it of its passion or joy. It may help us to understand God, but it may not direct us to experiencing God. People in this quadrant are prone to believe that “my theology is better than your theology.”

Quadrant Two: Personal Renewal

This quadrant (lower right) is primarily concerned with personal experience and authenticity. The goal of the Christian life is personal renewal and holiness of life. It seeks to avoid a dry intellectualism and believes that one’s experience of Christ leads to a transformed life. To really know is to be transformed by what one knows.

Sager quotes the following story to illustrate this quadrant:

“So you’ve been converted to Christ?”

“Yes.”

“Then you must know a great deal about him. Tell me: what country was he born in?”

“I don’t know.”

“What was his age when he died?”

“I don’t know.”

“You certainly know very little for a man who claims to be converted to Christ.”

“You are right. I am ashamed at how little I know about him. But this much I do know. Three years ago I was a drunkard. I was in debt. My family was falling to pieces. My wife and children would dread my return home each evening. But now I have given up drink; we are out of debt; ours is now a happy home. All this Christ has done for me. This much I do know!”

The emphasis here is on personal spiritual experience, a personally meaningful walk with God, identity and intimacy with God, repentance, renewal, and a positive, constructive witness in the world.

Testimonials are often part of worship. Praying is usually extemporaneous because it comes “from the heart.” Music is often less “classical” and more free – flowing. Worship tends to be less formal, believing that less structure creates more openness to the presence of the Spirit of God.

This quadrant makes several contributions to Christian spirituality. It reminds us that faith, if not really lived, is not faith. It challenges the church to practice what it professes. It encourages freedom, flexibility and creativity in worship. It will often make use of the arts because the arts appeal to more than just the mind. It encourages us not only to confess our faith in worship, but to share our faith in all of life.

When taken to extremes, there are also downsides to this quadrant. It can tend “toward emotionalism and excessive concern for feelings and right experience.” It can be anti – intellectual, making truth equal feeling. Its tendency to focus on victory can lead to an uncritical look at the reality of sin in our lives. People in this quadrant can come to believe that “my experience is better than your experience.”

Quadrant Three: The Inner Life

This quadrant (lower left) is most easily seen in monastic and ascetic movements throughout the history of the church. The focus here is away from words back to silence.

Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk (1915 – 1968) explained it this way: “Christianity is essentially a religion of the Word of God. It is easy to forget that this Word first of all emerges out of silence. Underlying the search for interior solitude is the basic posturing of self so as best to hear that Word when it is spoken.”

This quadrant is marked by a disciplined pursuit of an inner consciousness of God. It seeks to “provide a sense of rest, inner peace, and private solace apart from the tumultuousness of life round about.”

It seeks simplicity in order to create the possibility for a contemplative life, not in order to withdraw from the world but to engage the world in a more meaningful way. This desire for simplicity is illustrated in the following story:

In the last century, a tourist from the United States visited the famous Polish rabbi, Hafez Hayyim. He was astonished to see that the rabbi’s home was only a simple room filled with books. The only furniture was a table and a bench.

“Rabbi, where is your furniture?” asked the tourist.

“Where is yours?” replied Hafez.

“Mine? But I’m only a visitor here.”

“So am I,” said the rabbi.

In this quadrant listening is valued over speaking, and therefore it values the disciplines of solitude, fasting, simplicity and spiritual direction.

This quadrant challenges our assumption that busyness is the ultimate expression of spirituality; that our identity is found in what we do rather than in who we are.

In worship, it teaches us about the value of silence and space. It reminds us that the “Word became flesh,” not that “the flesh became words.”

When taken to an extreme, it also has downsides. It can lead to a withdrawal from life, a kind of quietism. It can lead to a passivity, the belief that all is mystery and nothing can be changed. Or it can lead to a mysticism that is so personalized it takes precedence over scripture or the community of faith.

Quadrant 4: Social Regeneration

This quadrant (upper left) focuses on social regeneration working toward a world that reflects the values inherent in the kingdom of God. Many of the prophets in the Bible would be part of this quadrant. It looks toward that time when God’s vision for the world will be fulfilled.

It is echoed in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., in a sermon shortly before his death, when he declared: “I fear no man because my eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” The goal is not simply on witnessing but on confronting the power bases of evil.

There are many contributions made through this quadrant. It reminds the church that faith requires courage. It reminds the church that its mission is in the world. It keeps the church connected to God’s vision of a cosmic redemption.

When taken to an extreme there are also dangers in this quadrant. It can easily lead to burnout because it seeks to create the ideal world. It can also work with a kind of tunnel vision: If you don’t get involved in a particular issue you are not really committed. It can overstretch a congregation’s resources because there are so many issues. It can turn into moralism or an outright rejection of culture.

If we ask the question, “Which quadrant would we most associate with Jesus?” I think the answer would be that he would be found in all four. For me, this is good news because in a day and age when many people think the church has come to an end, we discover that there are ways of knowing God and living out the Christian life that we have yet to encounter.

About Dale Woods

Rev. Dr. Dale Woods is principal of the Presbyterian College, Montreal.