I confess that I am not a Torontonian. Rather, after more than fourteen years living in Montreal I’m almost at the point where I could safely call myself a Montréalais.

So the challenge of loving Mayor Rob Ford isn’t my particular challenge. Rather, the newly elected Denis Coderre is my challenge – because no, I did not vote for him!

Nevertheless, the question of loving Rob Ford is a huge question these days, both for Torontonians and the rest of us across the country.

It seems safe to say that the number of those who love Rob Ford has been in precipitous decline in the past few weeks. Though it is also fair to say that there has been a large constituency of Ford-mockers and Ford-haters out there for some time. Over the past two years they have made a regular appearance on my Facebook feed, as well as in plenty of other spaces.

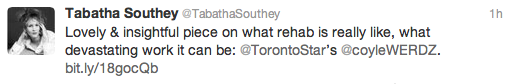

This weekend, the whole question of love him or hate him was brought to mind by three tweets by Tabatha Southey, who is a writer for the Globe and Mail. In the first tweet she referenced a Toronto Star article that explores the challenges and possibilities of rehab – where Rob Ford is expected/hoped to end up in the coming weeks:

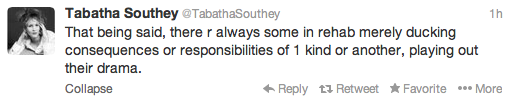

And then she followed that (hopeful?) tweet up with this one:

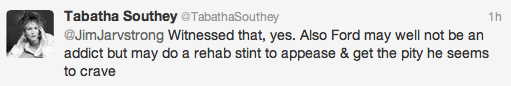

And then this one:

In other words, as much as she wants to say something positive about the possibilities of rehab for Rob Ford (the first tweet), she doesn’t want anyone to get the impression that she’s naïve (the second tweet) – naiveté being a particularly gauche fault for the modern, progressive journalist. So she loves Ford, but she’s also an eyes-wide-open REALIST (the third tweet).

All of which brought to my mind Kierkegaard’s Works of Love, in which he talks about what it means that “love believes all things,” words that come from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Corinthians. In exploring those words, Kierkegaard offers a critique of his contemporaries, a critique that fits equally well in our own culture today.

He says (words that I tweeted back at Southey): “We human beings have a natural fear of making a mistake—by thinking too well of another person.”

And, Kierkegaard adds: “[T]he error of thinking too ill of another is perhaps not feared, or at least not in proportion to the first.”

In other words, being a realist is prized above all in modern culture – and exposing oneself to the charge of being naïve is the worst kind of exposure. We want to show our knowledge of human nature, our familiarity with the hidden, malicious possibilities of the human heart. And a failure to exhibit and act on such knowledge means that you are a rube, or worse. And it’s not only superior journalists who embody this – we all embody this in our own way. The worst of all worlds would be to have someone come back at us and say that we were stupid: “You believed him, and you were WRONG.”

But in arguing that love believes all things, Kierkegaard asks:

But, to put it mildly, should it not seem just as stupid to us to have believed the evil or mistrustingly to have believed nothing—where there was good! Will it not sometime in eternity become even more than “stupid”…But here in the world it is not “stupid” to believe ill of a good person; after all it is an arrogance by which one gets rid of the good in a convenient way. But it is “stupid” to believe well of an evil person; so one safeguards oneself—since what one so greatly fears is being in error. On the other hand, the loving person truly fears being in error; therefore he believes all things.

Better, says Kierkegaard, to think too highly of another, and to assume the best in and of them, than to think too little of another.

For Kierkegaard, the argument has a theological foundation, for each human being is created in love, for love, by the God who is love. Each human being is one that Christ would draw to himself, in love. To love the other, by believing all things, is simply to believe that their being is rooted in love, and to relate to them and speak of them as if this is the most truthful thing that can be said of them.

To love the other is to prefer to be wrong in thinking too much of another, rather than to be wrong by thinking too little of him or her.

All of the natural objections will arise – including: “So we have to let him stay on as mayor, because we have to believe the best of him? Are you crazy!” Of course not! If he is unable to fulfill the requirements of his office, he should be asked to leave, helped to leave, or simply removed by those who may have the authority to do so.

But these political questions are only one part of the deeply personal way that people have loved him or hated him these past weeks and months.

For Kierkegaard (and the apostle?), to love Rob Ford, or anyone else for that matter, means to assume the best – and to not worry about looking naïve or like a rube if there is evidence (itself never incontrovertible) to the contrary.

Love believes all things…

Hmm – and a final question. Have I loved Tabatha Southey in what/how I’ve written?